As teachers, administrative staff and student support personnel, we know that a significant number of angry, depressed, addicted, and sometimes suicidal students are walking the halls of our schools. These youth are dealing with multiple traumas in their life, struggling to cope in an environment that requires maintaining control. Understanding how to engage these students in a healthy, positive way has become critical.

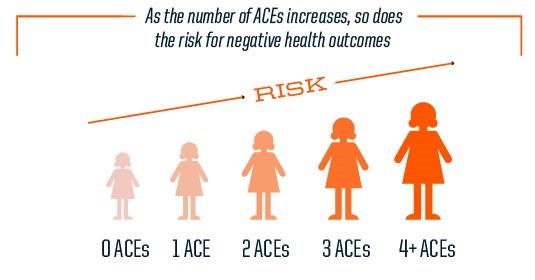

The 1998 Adverse Childhood Experiences study (ACEs), which sent standardized questionnaires to 13,494 adult members of a large HMO, found that a staggering 44 percent of respondents reported suffering sexual, physical, or psychological abuse as children, and 12.5 percent reported having a mother who had been treated violently1. Over the past decade, numerous studies have confirmed these percentages. The link between repeated ACEs and diminished classroom success is now well established. In schools and classrooms all over the country, educators are beginning to screen for ACEs and are trying to come to grips with how to be sensitive to the fallout from these experiences, both in their teaching practices and in exercising classroom discipline. Administrators are being challenged to modify approaches to discipline in order to avoid creating further trauma in the lives of their students.

Thanks to ACEs, change is in the air. Schools now face an avalanche of initiatives centered on trauma-informed practices. Legislation aimed at adjusting how schools approach discipline and chronic absenteeism has districts exploring creative procedures and interventions and implementing evidenced-based social-emotional learning (SEL) programs like Positive Behavioral Intervention & Supports (PBIS).

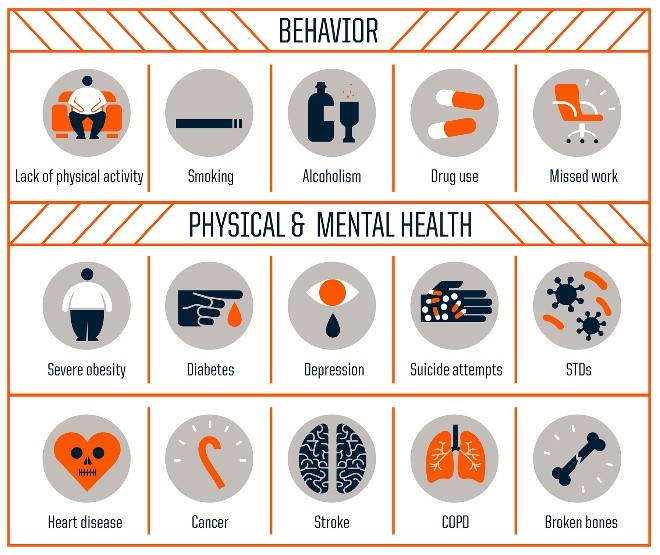

The impact of ACEs on student behaviors should not be underestimated; we have become increasingly concerned about school safety. Interventions based on trauma-informed practices change the way we approach disruptive and self-defeating behaviors. Increasingly, schools and their districts are using approaches based on tiered interventions. Many studies point to the effectiveness of these early interventions that interrupt the pathways to disruptive or violent behaviors. The simple approach of investigating, documenting, and providing effective interventions for behaviors when they first appear seems obvious. For many schools, however, this approach requires a shift from reacting to behaviors with traditional forms of discipline to understanding and responding to the underlying drivers of these behaviors.

The film “Paper Tigers” focuses on an alternative school in Walla Walla where ACEs became the central theme for dealing with a population of at-risk students. From teaching students to understand their own challenges resulting from adverse experiences to training staff how to be aware and sensitive to these challenges, the film documents the trials and successes experienced by everyone. For many educators, viewing this film completely changed the way they look at their school community.

The need for trauma-informed practices in our schools is clear, but where to begin? Child development psychologists Masten and Coatsworth identified three key factors common to all competent children:

- A strong parent-child relationship, or, when such a relationship is not available, a surrogate caregiving figure who serves a mentoring role;

- Good cognitive skills, which predict academic success and lead to rule-abiding behavior; and

- The ability to self-regulate attention, emotions, and behaviors2

These findings led to the development of the Attachment, Regulation, and Competency (ARC) model – building secure attachments between child and caregiver(s); enhancing self-regulatory capacities, and increasing competencies across multiple domains. Translating the ARC model into actions means schools must:

- Partner with families and strengthen traumatized children’s relationships with adults in and out of school;

- Help children to modulate and self-regulate their emotions and behaviors; and

- Enable children to develop their academic potential.1

In the book, Helping Traumatized Children Learn1, the authors suggest a flexible framework for implementing trauma-informed practices in any school community. The framework encourages evaluating each of the following six key elements from a trauma-sensitive perspective:

- School-wide infrastructure and culture;

- Staff training;

- Linking with mental health professionals;

- Academic instruction for traumatized children;

- Non-academic strategies; and

- School policies, procedures, and protocols

Obviously, this is a major paradigm shift. Here at the NWESD, we are committed to providing strong support to districts and schools as they move forward with trauma-informed approaches to school culture, discipline, and classroom instruction. Please contact us and let us know your needs for training and support.

For more information or questions please contact: Mike Stamper, Prevention Center Coordinator (360) 770-5831, mstamper@nwesd.org

– Ed

1. Helping Traumatized Children Learn

2. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. Lessons from research on successful children. Masten, AS & Coatsworth, J. Am Psychol. 1998 Feb; 53(2): 205-20.

Infographics used with permission from "The Truth About Aces"